Country Profile: Malaria and the Political Destabilisation of Mali

- Laura Dell'Antonio

- Dec 5, 2021

- 13 min read

Author: Laura Dell'Antonio

Mali used to be home to several pre-colonial empires, and the city of Timbuktu in the northern part of the country was once a crucial regional trading post and centre of Islamic culture. In 1892, Mali fell under French colonial rule and was ruled by France until after World War II. As nationalist movements mushroomed across colonial Asia and Africa, Mali finally gained independence from France in 1960. After gaining its independence, decades of instability have followed. The country has suffered droughts, rebellions, coups, and 23 years of military dictatorship until democratic elections in 1992. The current situation in Mali is both a humanitarian and security concern. The country is experiencing a socio-political crisis, increased insecurity in the central and northern regions, and climate hazards. Hence, the international community often describes it as one of the world's fastest-growing emergencies. The ongoing fighting between different groups and competition for control in the north has started to spread to central Mali and some areas in the south and has claimed 988 civilian lives in 2020. In 2021, an estimated 7.1 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance, requiring $498 million. So far, the situation has resulted in 46,930 Malian refugees and 401,736 internally displaced persons.

Conflict Origins

Most of Mali's population resides in the southern part of the country, leaving the northern part of the country, which occupies approximately two-thirds of Mali by area, sparsely populated. This area is mainly inhabited by the Tuaregs, a part of the Amazigh people, and Arabs. In the late 1980s and especially in the early 1990s, several military groups made up mainly of Tuaregs and Arabs began calling these territories of northern Mali and parts of Niger "Azawad," with the aim of gaining independence from these two postcolonial states. The Tuaregs and Arabs had felt abandoned by Mali and Niger and rebelled against the government in 1963, 1990, 2006, and most recently in 2012. Groups, including Islamist militant groups, have taken advantage of the instability, made territorial claims, and attacked both the Malian government and international security forces.

Fig. 1 | Political and Administrative Map of Mali ("Mali Map", n.d.)

The latest rebellion of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), a Tuareg separatist group, in 2012 was backed by a collection of Islamist militant groups including Ansar Dine, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the Movement for the Unity and Jihad in West Africa. The groups worked together to take control over territory in northern Mali. This rebellion resulted in a spread of anger over the government's response. It ultimately led to a military coup in March 2012, resulting in then-president Amadou Toumani Toure being deposed. This caused a power vacuum in Bamako due to the confusion and infighting, which in turn allowed MNLA and the Islamist groups to seize territory more efficiently and rapidly. By April, the rebelling groups were in control of nearly all of the northern regions and declared independence. However, the alliance between MNLA, Ansar Dine, and AQIM did not last long as the Islamists pushed to impose Sharia law, leading MNLA to break away in June. The Islamist groups gained control of Timbuktu and Gao, two important cities in northern Mali, and destroyed shrines while implementing harsh interpretations of Islamic rule.

In January 2013, the Islamist groups began pushing south towards the centre of the country, prompting the Malian government to request the French military to intervene by sending ground troops and launching air campaigns to push back militants. As the situation was not improving, the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) was created in April 2013 to combat extremism in the region. So far, more than 18,263 UN personnel have been deployed in Mali. Since MUNUSMA's establishment, it has often been called the UN's most dangerous mission as there are many attacks on peacekeepers. The launch of an international campaign against militant groups resulted in the spread of militants to neighbouring countries across the Sahel. This led France and the Group of Five for the Sahel (G5) countries (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger) to announce the creation of the G5 Sahel Force in February 2017. Operations began in 2017 with the aim to fight militant groups under an expanded mandate to move across borders in the Sahel region. The US also increased their presence in the Sahel region to approximately 1,500 troops and built a drone base in Niger to allow for strikes against groups across West and North Africa.

A further coup, led by Colonel Assimi Goita, occurred in August 2020. It followed months of escalating protestsagainst former President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta's administration. The March-April parliamentary elections sparked anger, but the underlying cause of the coup included discontent over the handling of the jihadist insurgency. The June 5 Movement, named after the first day of uprisings, triggered a showdown with the government, and protesters demanded that Keïta resign over the perceived failure of tackling Mali's eight-year jihadist conflict and the distressing economic situation of the country. On July 10, the rally turned violent and drastically escalated the political crisis. Protestors blocked bridges, stormed the premises of state broadcasters, and attacked the parliament building in Bamako. The official casualties of the three days of clashes included eleven dead and 158 injured, making it the bloodiest bout of political unrest Mali had seen in years. Regional organisations, including the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), pressed for the military junta who took power to form a transitional civilian government predicated on civilian rule. After Bah Ndaw was named President, Moctar Ouane was named Prime Minister, and Assimi, the coup leader, was named Vice President, ECOWAS lifted the sanction, and the African Union (AU) lifted Mali's suspension.

Less than nine months later, in May 2021, the military carried out a further coup. They arrested and detained President Ndaw and Prime Minister Ouane. This was the fifth coup Mali experienced since its independence in 1960. Assimi Goita, who led both the coup in August 2020 and the one in May 2021, assumed power and said the new prime minister would soon be announced. Goita was sworn in as interim president and stated that he would oversee the transition towards a democratic election. Soon after, the appointed opposition leader and former minister Choguel Maiga was named Prime Minister. The AU and ECOWAS responded by suspending Mali, and the AU has threatened sanctions against the military if it does not produce a transitional government led by civilians. ECOWAS demanded that the military junta adhere to an 18-month transitional government timeline established in August 2020 with Ndaw as president and Goita as his Vice. Additionally, the timeline outlines plans for future elections to be held in February 2022; however, these are in jeopardy due to the military's recent seizure of power. Goita's advisors have suggested that these elections may be delayed. Maiga then said that the date could be postponed by "two weeks, two months, a few months" to avoid contested validity. On October 24, a UN Security Council Delegation representative announced that Mali's interim authorities would confirm a date for a post-coup election after national reform consultations in December.

The presence of numerous counterterrorism forces and internationally supported military operations did not prevent violent attacks. The major terrorist networks and militant groups present in the country remain a threat, and attacks against peacekeepers continue. Moreover, France announced that Operation Barkhane, its fight in Mali, would end, and the military would withdraw its troops and refocus towards an international counterterrorism effort in the Sahel. There has been a continued strengthening of the militant groups in Mali and a spread to neighbouring countries across the Sahel, which could lead to AQIM and IS establishing new safe havens and destabilising the region through militancy and terrorism. Additionally, the northern areas of Mali remain a transit point for young migrants from Western Africa who are looking to travel to Europe via Algeria and Libya. The weak economy of the country and lack of job opportunities has resulted in people turning towards trafficking and smuggling of drugs and migrants as a source of income, which is also the primary way that militant groups across the Sahel fund their campaigns.

The situation in Mali remains dire. Human Rights Watch is concerned after a spate of alleged summary executions, enforced disappearances, and incommunicado detentions by government security forces. The upheaval caused by the conflict also adds to the food shortages among vulnerable people, and the erratic rain pattern in the country is putting a strain on the limited food sources. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has added to the challenges the healthcare system faces and has impacted access to healthcare and food security in rural areas. In areas affected by conflict, 23% of healthcare facilities are not functioning, and only 5% of the IDPs have safe access to water which is below the national average of 68.8%. In the northern and central regions of Mali, around 1,200 schools have been closed due to the conflict, and the insecurity is affecting over 391,000 children and 7,800 teachers. Furthermore, the security situation for peacekeepers and humanitarian aid workers remains dangerous. In 2020 alone, Mali registered 200 security incidents affecting humanitarian non-government organisations (NGOs). This fragility of humanitarian access highlights the need to reaffirm humanitarian mandates and principles to maintain access and provide much-needed assistance. Meanwhile, Mali still faces challenges to health and well-being that were present prior to the most recent conflicts.

Malaria in Mali

The primary cause of morbidity and mortality in Mali is malaria. Mali, a country with a population of 19.6 million, experienced approximately 6.5 million cases and 11,700 deaths due to malaria in 2019 alone. The entire country is considered at risk; however, transmission varies across the five geo-climate zones in the country. Although the number of cases fell by 13% and deaths by 21% in populations at risk in Mali between 2016 and 2019, the country still ranks amongst the top ten countries with the highest number of malaria cases and deaths worldwide, contributing 3% of the global cases and deaths. Several factors contribute to the high malaria burden that Mali, and many other countries, face, including the underlying intensity of malaria transmission, poor access to care and substandard malaria intervention coverage, funding constraints, and sociodemographic and epidemiological risk factors. Prevalence of malaria varies widely across regions in Mali, from 1% in Bamako to a maximum of 30% in the Sikasso region, which is the southern-most region.

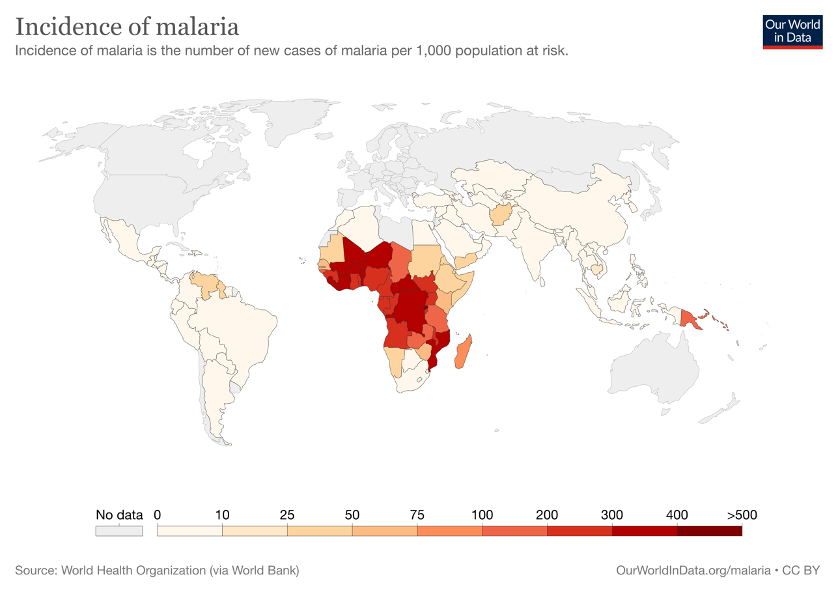

Fig. 2 | Incidence of malaria worldwide (Roser & Ritchie, 2019) Incidence of malaria is the number of new cases of malaria per 1,000 population at risk

Malaria is a serious and sometimes fatal disease for which nearly 50% of the world population was at risk in 2019. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that in 2019, there were 229 million clinical cases and 409,000 malaria-related deaths, with 67% of deaths occurring in children under the age of five. Africa carries by far the greatest burden from malaria, accounting for 94% of cases and deaths in 2019. Malaria is caused by a parasite that infects Anopheles mosquitos, which can then transmit the disease when feeding on humans. There are five types of malaria parasites that are known to infect humans: Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae, and P. knowlesi. Although P. knowlesi can infect humans, it naturally infects macaques in Southeast Asia; hence, infections with this parasite are often referred to as “zoonotic” malaria. P. falciparum is known to be the deadliest of the five parasites and is most prevalent on the African continent. Outside of sub-Saharan Africa, P. vivax is the dominant type.

Fig. 3 | Malaria Lifecycle Malaria's lifecycle from mosquito to human, back to mosquito

Most malaria infections are due to a bite by an infective female Anopheles mosquito. Uninfected mosquitos can become infected by feeding on an infected person. The mosquito can then, in turn, infect more humans. When the parasite enters the body, it travels to the liver where some types can lie dormant for up to a year. Once the parasite has matured, it leaves the liver and starts infecting red blood cells. The infection of red blood cells is usually when the onset of symptoms occurs, and it is the state in the infection when a mosquito can get infected by biting the infected individual. Other, less common methods of transmission are from mother to unborn child, through blood transfusions, or by sharing needles that are used to inject drugs. Malaria symptoms usually include fever, headaches, and chills that generally occur 10-15 days after the infective mosquito bite. As these symptoms are often mild and very similar to other diseases, it is often difficult to recognise it as malaria. P. falciparum can progress to severe illness and death within 24 hours if left untreated. However, illness and death from malaria can be prevented, for which early diagnosis and treatment is key, especially to prevent further transmission.

The WHO recommends that malaria infections are confirmed using parasite-based diagnostic testing either through microscopy or through a rapid diagnostic test. The best available treatment is artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT), especially for P. falciparum. Prevention methods for malaria can be categorised into three categories: vector control, preventive chemotherapy, and vaccines. Vector control mainly focuses on the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS). Preventive chemotherapy is the use of medicines to prevent infection and the consequences of infection to complement ongoing malaria control initiatives. It includes chemoprophylaxis, intermittent preventive treatment of infants (IPTi) and pregnant women (IPTp), seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), and mass drug administration (MDA). Lastly, since October 2021, the WHO has recommended the use of the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine among children living in regions with moderate to high P. falciparum transmission. The WHO Global technical strategy for malaria 2016-2030 is meant to help guide and support regional and country-wide programs as they work towards reducing the burden of malaria by controlling and eliminating the disease. It lays out ambitious targets for 2030 that include: reducing case incidence by at least 90%, reducing mortality rates by at least 90%, eliminating malaria in at least 25 countries, and preventing a resurgence of malaria in all countries that are malaria-free.

In Mali, malaria is endemic in the central and southern part of the country where the majority of the population lives, while it is epidemic in the northern region due to the limited viability of the mosquitos that transmit malaria in the desert climate. Mali has stable malaria zones, where transmission occurs throughout the year with some seasonal variability, unstable malaria zones with intermittent transmission (mainly in the Sahelian-Sahara), and sporadic malaria zones which is typical for the Sahara and where the population has no immunity as a result. Peak malaria transmission in Mali occurs from June to November in the south of the country and in July/August in the northern regions. Both the A. funestus and A. gambiae transmission vectors can be found in Mali, and the incidence of P. falciparum is greater than 85% in the country. Antimalarial drug resistance is beginning to emerge as a threat to ongoing control efforts, especially in the Greater Mekong subregion. However, multi-drug resistance strains of P. falciparum are present in all areas of Mali that are affected by malaria.

Fig. 4 | Epidemiological profile of malaria in Mali 2017 (Malaria Country Profile Mali, 2018) Confirmed cases per 1000 population (left); Plasmodium falciparum parasite prevalence (right)

Although a recent decrease in the incidence of malaria has been seen in Mali, it remains an issue that needs continued addressing. A new malaria control program was developed by the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) and the Ministry of Health (MOH) for the period 2018-2022. The program aims to decrease malaria mortality and morbidity by 50% from levels observed in 2016. By 2030, Mali aims to eliminate malaria. There are numerous ongoing initiatives and programmes supported by a variety of organisations to help Mali in this mission.

The U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative has supported Mali in the fight against malaria since 2007, and in 2020, allocated a budget of $25 million to support and build on the investment made by the Government of Mali in coordination with stakeholders. Additionally, the NMCP is supported by numerous organisations, such as UNICEF, the WHO, USAID/PMI, and ACCESS-SMC, to provide seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) programmes. This is a very effective intervention to prevent malaria in vulnerable populations. As part of the program, monthly doses of antimalarial drugs are administered to children aged 3-59 months during peak malaria transmission season. A recent study in Kita, Mali showed that when SMC programs are implemented at fixed point distributions through the routine health system, they are highly cost-effective. In 2019, NMCP implemented a SMC campaign in nine health districts in the Moopti and Ségour regions. The campaign reached 725,000 children under five years of age. The campaign not only involved the distribution of medication but also training and supervision of thousands of SMC staff, as well as the creation of mobile money systems to pay healthcare workers.

Mali continues to have high access and use (90% and 79%, respectively, in 2018) of ITNs, and the proportion of pregnant women and children under five (84% and 78%, respectively, in 2018) sleeping under ITNs remains high. The current goal is for Mali to reach universal coverage of bed net distribution by 2022. Although significant progress has been made in Mali, one can hope that the ongoing conflict in the northern region, which is slowly spreading to the central and southern part of the country, will not result in a deterioration of the public health situation. In the areas affected by conflict, 23% of the healthcare facilities are not functioning. If the conflict continues to spread south, areas that experience a much higher prevalence of malaria will be impacted. Having accessible healthcare facilities is key to controlling and reducing the burden that malaria causes. Thus, to continue seeing success in reducing malaria, the government and international community need to maintain the effort to stabilise Mali politically, in addition to providing aid that supports health infrastructure.

Next Steps

Mali is currently at an inflection point. It has recently experienced two coups, interethnic and terrorist violence is moving south towards the capital Bamako, and France is changing its strategy in the Sahel. Hence, the international community needs to act now to stabilise the country, preventing Mali from spiralling further down. Some lessons can be learned from Afghanistan; however, Mali is a country that must be understood in its own right. In addition to the country's unique ethnic and political dynamics, some key differences are that the terrorists in the Sahel do not have the equipment or experience that the Taliban has and that the neighbouring countries are not providing shelter and support. Therefore, it is essential to empower local partners in Mali and shift towards a lighter footprint without generating a collapse. Moreover, there needs to be sustained public support for intervention, and the coalition needs to be managed well. A southward movement of violence towards the demographic and economic heart of the country has been seen. So far, the Bambara majority and elite has not felt compelled to invest militarily and politically in the north, where Bamako traditionally have not had much control. With an increasing threat further south, it may incentivise the government towards more responsible behaviour. Coordination between the different forces in the region, the Malian Armed Forces (FAMa), the European Union Training Mission in Mali (EUTM), MINUSMA, and the G5 Sahel Joint Force, remains a complex task. A platform for regular meetings has been introduced for the different forces to communicate, which appears to have helped. Lastly, for Mali to truly own the stabilisation process, Europe must avoid creating dependence and must prevent establishing a presence of which only the elite benefits, which was one of the main problems that led to the terrible failure of the Afghan government and army.

This article was prepared by the author in their personal capacity. The opinions expressed in this article are the author'a own and do not reflect the view of their place of employment.

Comments