Country Profile: Malaria and the Crisis in Burundi

- Brian Samuelson

- Jan 24, 2022

- 11 min read

Updated: Jan 28, 2022

Author: Brian Samuelson

Countries are experiencing unprecedented emergencies, which are turning into humanitarian crises. The International Rescue Committee (IRC) released its 2021 "watch list" of ongoing humanitarian crises expected to experience detrimental effects over the coming years. However, several countries, unfortunately, did not make the “watch list.” The Burundi humanitarian crisis, well known around the globe, began in 2015 but has become a forgotten crisis. The Republic of Burundi is in the African Great Lakes region of east Africa. Burundians are crying out for help as they experience economic decline, famine, disease outbreaks, and political suppression. Many are experiencing forced displacement to escape the suffering.

Conflict Origins

It has been a long downward movement mixed with false hope for the people of Burundi. They have faced the repercussions of a 12-year civil war between Burundi's ethnic Hutu rebels and the Tutsi army that inflicted pain and suffering. In 2000, the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement was adopted as a framework to promote peace and stability, moving away from Burundi’s violent past. As a result, the civil war ended in 2005 with Hutu rebel leader Pierre Nkurunziza as the incumbent president. However, political conflict began to escalate again in 2015 when Nkurunziza went against the Arusha agreement and the 2005 constitution, which prohibits presidents from running longer than three terms. However, the CNDD-FDD party claims there was no violation because Nkurunziza's first term did not count, as parliament appointed him. This event was the spark that resulted in the Burundi humanitarian crisis.

Once President Pierre Nkurunziza was nominated as the CNDD-FDD party's candidate with his Hutu nationalist agenda, protestors began flooding the streets of Bujumbura. This affair triggered several months of protesting and a failed coup d’état. As a result, police forces and the state-sponsored militia, Imbonerakure, began provoking mass atrocities around Burundi. Burundians view the militia as murderous, militarized, powerful, and uneducated. Imbonerakure is suspected of having close to 50,000 members across the entire country with the goal of constructing a campaign of intimidation and brutality. Their purpose was to help President Nkurunziza win the election for his third term. Several reports released stated that the Imbonerakure was maliciously attacking protestors with machetes and grenades. In addition, military officers were equipping Imbonerakure with weapons for sole use on protestors. The group is a significant threat to Burundi's peace and is an escalating factor in the humanitarian crisis.

As a result of the failed coup, President Nkurunziza purged his army, targeting all soldiers who served the Tutsi government during the civil war. The military purge caused more rebellious militias to coalesce and wreak havoc around the country. The newest and most prevalent militia group was the Republic Forces of Burundi (Forebu), created following the failed coup in 2015. They were composed of highly skilled Burundian military personnel discharged from the army who opposed President Pierre Nkurunziza's power. The Forebu became later known as the Popular Forces of Burundi (FPB) and established themselves in the eastern parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo. FPB rebellious leaders were Major General Jérémie Ntiranyibagira and Lieutenant Edouard Nshimimana. They intended to take control of the country while inflicting extreme violence towards the Hutu group. Militias like the FPB have caused cyclical violence outbreaks against the military. The government has resorted to the traditional violent atrocities that the country faced during its civil war. State agents have killed 1,115 individuals since the beginning of the crisis. However, this number is likely inaccurate since President Nkurunziza has suppressed all external reporting on the country.

Refugee and IDP Situation

Despite the lack of information in the region, there is enough evidence to prove that the crisis is not improving. There are approximately 107,870 internally displaced persons (IDPs) flocking to different providences in Burundi; this is a result of natural disasters in the region that are exacerbating the crisis. Most IDPs are migrating to Bujumbura Mairie for its proximity to Lake Tanganyika for water, work, and to run from violence. In a population of approximately 12 million people, over 333,700 of Burundians are seeking refuge in neighboring countries, with only 40% of refugee funding needs being met. This statistic resulted in the UN refugee agency chief, Filippo Grandi, coining Burundi as "one of the most forgotten refugee crises globally." According to Humans Rights Watch, as of October 2020, there are more than 150,000 Burundian refugees in Tanzania. The main refugee camps are in the Kigoma region. Those are Nduta, Nyarugusu, and Mtendeli. Despite their intention to seek refuge away from their hostile country, many Burundians could not escape the violence. The Tanzanians do not respect the Burundians and have enforced arbitrary arrests and abductions by Tanzanian security forces trying to force them to return to Burundi.

Furthermore, there are 40,601 Burundian refugees in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 47,669 in Rwanda, and 51,410 in Uganda. A significant fear from the Burundi crisis is that neighboring countries do not want the crisis to provoke their own leaders into pursuing reelection for multiple terms. This circumstance could potentially result in a similar humanitarian crisis in their homeland.

Barriers to Access for Food and Health Services

However, of all the Burundian refugees, most of them are between ages 0-17. With socioeconomic tensions and violence rising in Bujumbura, children are viewed as the most vulnerable. They are fleeing the country as they face an increased risk of child exploitation and trafficking. These risks further contribute to their likelihood of survival, access to education and vaccinations, and overall developmental challenges. With the combination of environmental flooding factors from El Niño, people find it challenging to locate public health services. This has resulted in rising risks of HIV transmission, unsafe delivery for pregnant women, and communicable disease outbreaks. Many children born into the crisis are also not vaccinated from diseases and are therefore more susceptible to infection. The 2019 Global Health Index (GHI) reported that Burundi ranks in the bottom percentile of countries for pandemic and epidemic preparedness. It has an index score of 22.8, ranking the country 177 out of 195 countries. As of May 2020, Burundi reported 42 cases of COVID-19 and one death. This is surprising considering the rest of Africa had reported over 63,521 cases at that time. However, the ongoing crisis and low accessibility to testing can be the answer behind the data. During this time, the Burundians also faced a measles outbreak that began in a temporary refugee camp in Cibitoke and spread to permanent camps hosting more individuals. The reported outbreak was mainly among children aged nine months to 5 years who were unvaccinated. The management of the measles outbreak forecasted the management of SARS-CoV2, and correct data will not be available because of the suppression from President Nkurunziza.

Healthcare disruption is not the only contribution to the crisis; there has also been a deterioration of food security. Burundians rely heavily on subsistence farming for food. The Emergency Food Security Assessment conducted by the WFP and FAO shows that the most affected provinces in Burundi from food security are Cibitoke, Kirundo, Rumonge, Makmba, Bujumbura Rural, and Bujumbura Mairie. The food shortage resulted from political instability and suspension of foreign aid that escalated the economic decline. Without good agriculture production and farmers seeking refuge, the supply chain becomes disrupted. The assessment notes that one in of five households is food insecure. These rate translates to around 648,000 people, and of these individuals, children and women have been shown to face malnutrition the most. As a result, the Blanket Supplementary Feeding Program began in Kirundo and Makamba with the hopes of mitigating malnutrition of pregnant women and young children.

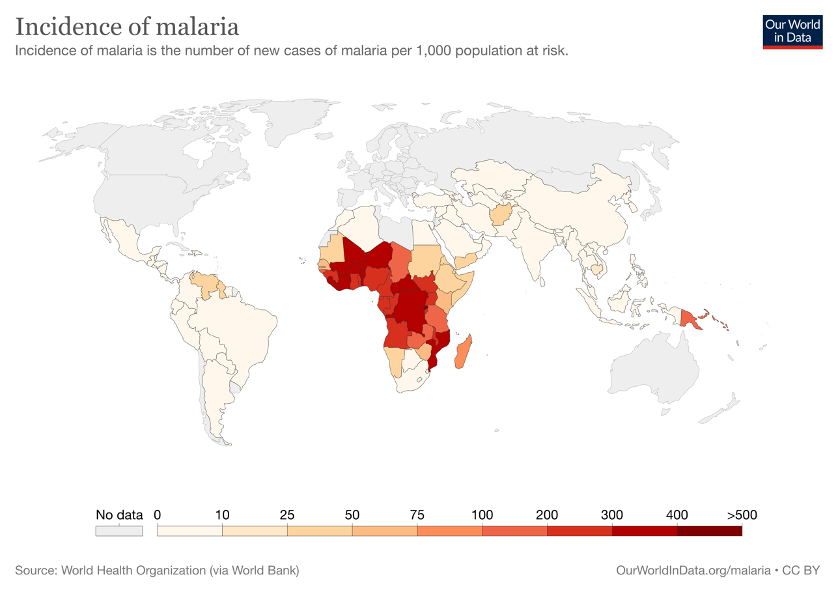

Malaria

Malaria is a vector-borne disease that can be caused by five different obligate parasite species. The two most virulent species of parasites are Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax. Burundi has an incidence rate of over 86% for Plasmodium falciparum. However, the entire sub-Saharan region of Africa is susceptible to malaria outbreaks. Malaria has a multiple route transmission cycle. An infected female Anopheles mosquito can directly infect a human, or an uninfected mosquito can bite an infected human and then transmit the disease to more human hosts. After an bite by an infected female Anopheles mosquito, the incubation period varies from 7 to 30 days. However, the incubation period is shorter with P. falciparum. This is a significant contribution to its high transmission rate in Burundi.

Infection may result in a broad spectrum of symptoms, ranging from mild to severe. It is reported that all clinical symptoms are caused by the asexual erythrocytic cycle. Hemozoin pigment and other toxic substances accumulate in the red blood cell and are released into the bloodstream when the infected red blood cells lyse and release invasive merozoites. The human body's response is to stimulate macrophages due to the recognition of foreign glucose phosphate isomerase and other toxins, resulting in fever, anemia, jaundice, chills, headache, body aches, and sweats, and other severe pathophysiology associated with malaria.

Malaria in Burundi

Infectious disease outbreaks have dramatically impacted the humanitarian crisis in Burundi. Throughout the provinces of the Republic of Burundi, the accessibility to healthcare is a significant issue for responding and finding solutions to mitigate diseases. Multiple diseases and epidemics are spreading and escalating suffering in the country. The fragile healthcare system has faced detrimental effects from ongoing malaria outbreaks. Strengthening the healthcare infrastructure in Burundi has been a task that organizations and world leaders have sought to solve for several years. However, the ongoing conflicts in the country have made it difficult. Nevertheless, there have been continuous efforts to mitigate the spread of communicable diseases.

With a population 12 million people, Burundi has reported 8,571,897 malaria cases, including 3,170 deaths, through the beginning of 2020. The most affected populations are children under five years of age and individuals over the age of 60. Within these age groups, mortality rates are relatively high when treatment is not initiated. The three distinct epidemiological transmission zones are low altitude areas (epidemic-hyper), central high plateaus (epidemic-prone), and the Cong-Nile crescent. Cases peak during the rainy seasons, which is when mosquito populations spawn, but cases are ongoing throughout the year. Therefore, Burundi is considered a malaria concerned area, which has contributed to residents treating themselves without diagnostic confirmation. It is recommended that clinical testing be conducted to confirm parasites in the blood via microscopy or rapid diagnostic tests. Additional laboratory testing can be done for malaria confirmation by examining blood samples of anemia, thrombocytopenia, the elevation of bilirubin, and aminotransferases.

There have been severe barriers to developing a malaria vaccine, which has been in development since the 1960s. This is mainly attributed to the complexity of the parasite's life cycle and insidious nature. However, on October 6, 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the widespread use of RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine among children residing in sub-Saharan Africa with moderate to high Plasmodium falciparum malaria transmission. The vaccine is a safe, three-dose series plus a booster dose, which causes a 30% reduction in severe malaria. There is another promising vaccine, which consists of non-infectious whole sporozoites manufactured by Sanaria. It is shown to be safe and provides protection against malaria when administered intravenously. However, further studies need to be done before it gets recognition from the WHO. Generally, malaria is curable; before the development of the remarkable RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine, therapies were the prominent source of mitigation. Prescription drugs are used to treat malaria. In Burundi, atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline, or mefloquine are the preferred treatment to prevent malaria. However, there have been complications from multi-drug resistance, such as chloroquine, resulting in all regions being high-risk territories.

The epidemiological condition in Burundi has remained an area of focus since 2000, leading up to the acknowledgment of a malaria epidemic in 2019. The rate of confirmed cases increased from 9.2% in 2000 to 70.6% in 2019 and has shown low likelihood of slowing down. Leading up to the humanitarian crisis, Burundi has reported having an inadequate health care system even though they have been a destination for investment through the 2012 Burundi Health Workforce Observatory and Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations. This is likely due to the instability of the political regime and the capacity to embrace the healthcare system. During this time, the primary player involved was the incumbent president, Pierre Nkurunziza, a totalitarian. He was more concerned about reelection than declaring a national emergency to ensure the health of his people. It is also apparent that the health information system suffered tremendously due to quality issues and skill gaps in infectious disease surveillance. Until 2005, most of the malaria testing was performed using light microscopy and reported on paper. It was not until 2018 that the country shifted to 75% of testing done by rapid diagnostic tests. This has improved the quality of surveillance.

Cross-Cutting Efforts to Address Health Challenges in Burundi

The main concern for refugees and residents in Kirundo, Cibitoke, Rumonge, Makmba, and Bujumbura is not personal health concerns but rather surviving the violence around them. The ongoing violence has created a generalized vulnerability in the population. However, since malaria has been acknowledged as an epidemic, there have been more resources to mitigate infection. Health teams from the Global Fund, UNICEF, and USAID distributed 6.8 million bed nets in 2020 to prevent mosquitos from biting individuals at night. Satellite clinics were made more accessible and more ready to deploy in remote communities, and spraying systems targeted nine of the most affected districts of Burundi.

In a recent report by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), it was stated that the lack of preventable measures, migration of low immunity people, global warming, and mosquito behavior had escalated malaria cases in Burundi. It was also reported that “the national malaria outbreak response plan, which is currently being validated, has highlighted a lack of human, logistical and financial resources for effective response.” It is essential to correct and fill the gaps to ensure malaria numbers will decrease and not reach epidemic levels again. There needs to be a redirection in prevention measures, and several organizations proposed ways to solve funding scarcity for the healthcare systems and are willing to supply materials to provide necessary progress. In April 2020, the World Bank and International Development Association (IDA) put forward a $5 million grant to reinforce the Burundi health care system. These funds will aid in the country's ability to perform more testing and treatments for all existing diseases. The International Rescue Committee (IRC) placed several goals to provide aid to Burundi in 2020. The IRC determined it will provide better multidisciplinary healthcare for Burundi, starting with the basics. For instance, the IRC intends to assemble handwashing stations, boost hygiene knowledge, and address sanitation issues. Small steps like these can make a massive difference for a country experiencing prevalent infectious disease outbreaks. In the upcoming years, there is hope that the ongoing malaria crisis in sub-Saharan Africa will be contained by new vaccines, therapeutics, and public health programs.

The Conflict Moving Forward

The Burundi humanitarian crisis could have been avoided with a more robust government strictly following its constitution and policies. The first step where the Burundi parliament made a mistake was electing Pierre Nkurunziza, a rebellious leader, as their president. He did not have any remorse for shedding blood on people during the civil war, so why would his behavior change once he obtained more power? Furthermore, President Nkurunziza had several years to learn how to escape political repercussions for his malicious behavior. Therefore, early warnings are not the dilemma, but avoiding early action is. The African Union (AU) needed to seek help from the United Nations earlier and implement their African Prevention and Protection Plan in Burundi. The country's political history and violence should have never been taken for granted. It may have been a thought in the minds of global leaders, but there needed to be a proactive plan rather than a reactive solution. Humanitarian crises are only going to become worse if global leaders do not do their part. The massive genocide in Rwanda and the civil war in Burundi should serve as learning examples. Fear and political instability are the root causes of many humanitarian crises. These will inevitably result in innocent deaths and suffering. Like the Rwandan genocide, the danger is heightened particularly among the most vulnerable populations, namely women and children. Therefore, it is essential to empower the powerless and ensure the children of the future are protected and educated.

This article was prepared by the author in their personal capacity. The opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not reflect the view of their place of employment.

Comments